If you are just beginning this journey with us, we are so thrilled to have you as a colleague. I’m confident you’ll find our online program to be comprehensive, challenging, and responsive to your needs. If you are continuing with your studies and are beginning a new term of research or coursework, I hope you’re as excited as I am for another year of learning, growth, and opportunity.

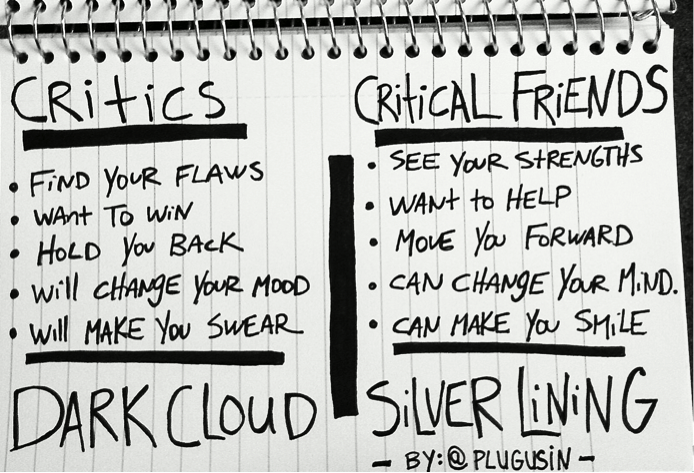

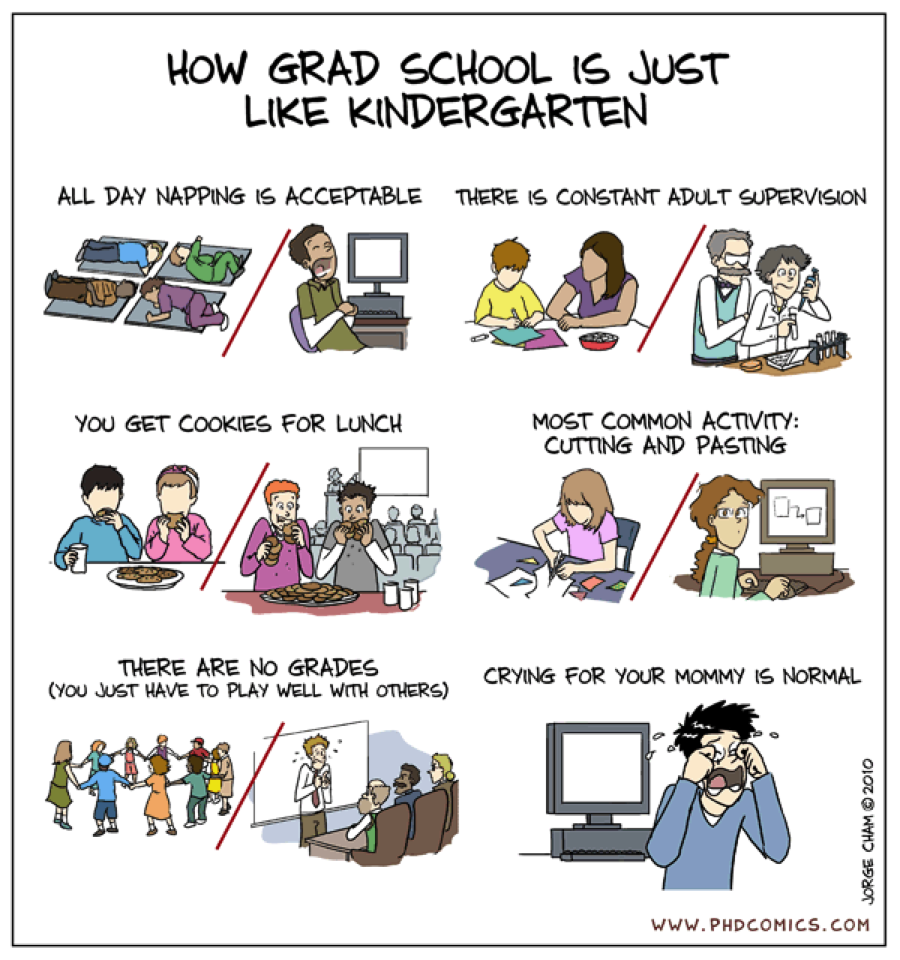

Make no mistake; graduate level studies are designed to prod, provoke, and problematize your thinking, which frequently leads to temporary periods of discomfort and discontentment. However, rest assured that it’s worthy work, and that you are not alone throughout this rewarding process. Though we may be separated by geographic distance, know that your classmates and professors are only an email, phone call, or Skype away. We are all in this together; never feel afraid to reach out for support.

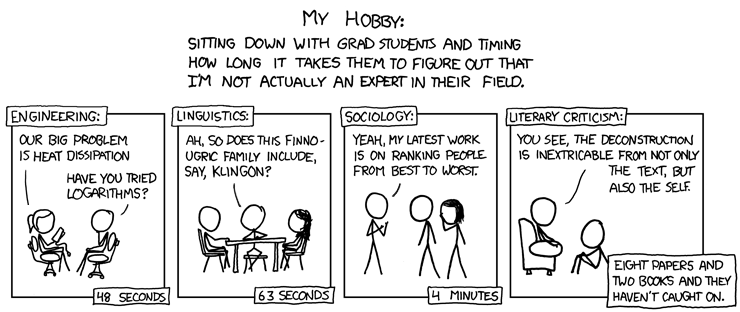

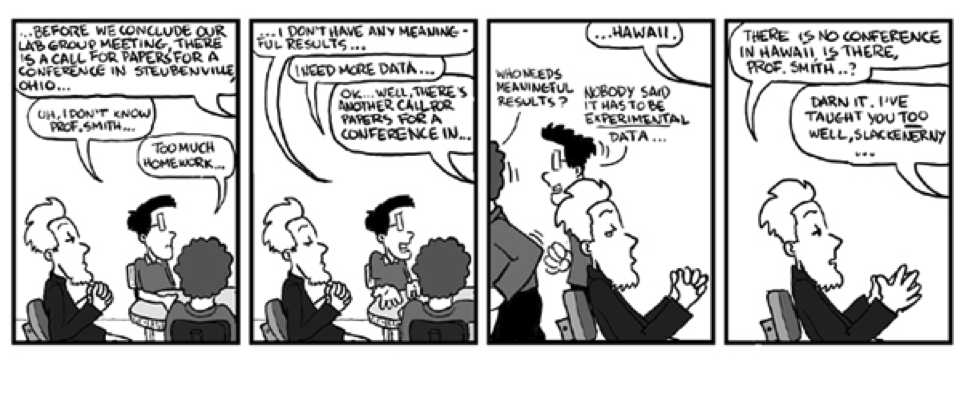

Over the past year, my colleagues and I have wrestled with Impostor Syndrome, attended conferences, gone through the process of thesis approval, engaged in field research, attended group research discussions, built critical friendships, and balanced the demands of coursework with our familial, professional, and personal obligations. Through all of this experiential learning, I can reflect upon my first year in the program, and offer a few tips for success that I’ve clumsily accumulated by stumbling through the challenges presented by the rigours of my chosen route.

If you have anything to add to this list, please feel free to do so in the comments below, or on our Facebook page.

-

The Medium is the Message, and the Process is the Product

Paying homage to Marshall McLuhan’s theory, the process of graduate work is simultaneous a process, and a product. In other words, it’s the journey, not the destination. The process through which you go through your studies and research work is also an incubator for complementary skills that will be essential to your long-term development; time management, academic writing, reflection, resilience, adaptability, and criticality. The medium (the route your graduate work takes) and how you engage with it will ultimately shape your message.

What does this mean?

Be kind to yourself: mistakes are a necessary part of the process, inherent to your experience. I’m currently listening to transcripts of when I was out in the field researching, and sometimes I cringe at mistakes that I make. Congratulate yourself for being brave enough to go outside of your comfort zone, take the lesson you need from the mistake, and move on.

Another tip? Experimentation. Play around with your scheduling (as best you can), figure out your peak reading and writing times through trial and error, and be willing to try again. It’s taken me a year to make peace with my own internal clock, but now I can be much more responsive to my state of mind and energy levels. When I first started and was focused on coursework, I’d be on the discussion boards from 7am- 11am, and again from 7pm-9pm, to respond to what had been said during the day. That worked really well for me. However, I had to completely shift this schedule when I started working on my thesis. If you’re working full time, you may not have as much of an option, but you may find that waking up at 5am to complete your work for the day is preferable to beginning your work at 6pm. Trial and error, friends…trial and error.

Reflect: do frequent check-ins with yourself. Due dates coming up? Research proposal coming down the pipeline? Neglecting any other areas of your wellbeing? Any “aha!” moments? Write in a journal, go for a long walk or run, and allow yourself the time and space to reflect on your work.

-

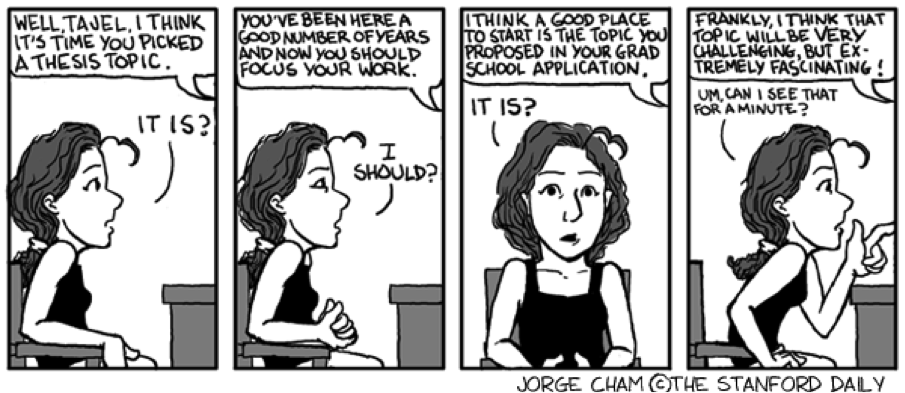

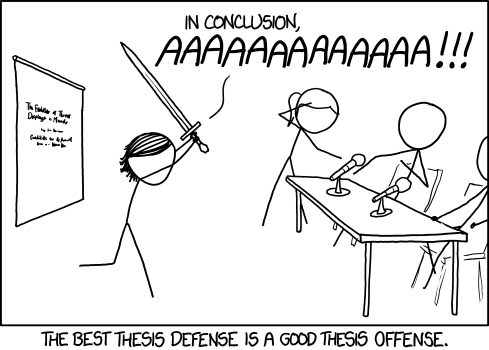

Chose your route as soon as you can

We have many posts on the three routes and the differences between the three, but knowing from the get-go what my path was helped me to hit the ground running. See this post for more information about each route. Start a conversation with your Faculty Advisor as soon as you’re able so that you can feel confident moving forward, even if you chose to focus solely on coursework and the research project and seminar. Knowing from the star that I wanted to do a thesis helped me make decisions, keep an eye out for opportunities, and tailor my coursework so that I could incorporate the research I performed for class credit into my thesis. I basically just had to tweak my research proposal from Research Methods in order to be approved for thesis, while keeping a copy of my ethics paperwork printed and by my side to complete them all simultaneously. Work smarter, not harder.

-

Recognize your distractions

I’m a news junky, and am frequently on Facebook to see what headlines come up on the various news sources that I like and follow. As a result, I’ve had to install blocker software onto my computer to prevent me from accessing both it and YouTube. I use Self Control, it’s free and has helped me more than I’d like to admit.

Just this past month, I realized that I could get distracted by random thoughts and ideas that floated through my head (movie titles, a book that I just remembered that I had wanted to read at some point, I wonder what ever happened in season 6 of The Vampire Diaries…etc.) and suddenly I’d look at the clock and I’d been on Wikipedia for an hour. So I created my official Distraction Journal (it’s an orange moleskin). When I’m working and I get a thought that is starting to itch, I just write it down, so it knows that I’ll get to it when I’m done my work. Then it can stop bugging me and I can keep writing. It’s a simple fix, but it’s very effective.

-

Back. It. Up.

This past October, I spilled a travel mug of tea all over my keyboard of my Mac, which then proceeded to turn itself on and off, until it turned itself off and was unresponsive. I put it in rice, and brought it into tech services, who were fortunately able to resuscitate my poor baby. Since then, I’ve been backing up my hard drive once or twice a week. All of my important documents are additionally backed up on Google Drive.

Back it up. Then back it up again. Have you backed it up yet?

-

Be present

Physically, this might be a challenge, depending on where you’re studying from. But our bi-weekly graduate meetings offer a Skype option. If the timing doesn’t work for you, try writing a post for the blog, or consult with your faculty advisor or supervisor about a conference near you that you can attend or present at. The more time you spend as an active, present member of the community, the stronger your resolve will be when the going gets rough, because you’ll feel the invisible bonds of community.

Is there anything I’ve missed? Sound off in the comments, either below or on Facebook. Good luck, everyone!