The following is a dialogue between Laura McRae and Marianne Vander Dussen, both in their first year of the Master’s program. We decided to build our blog post to capture the conversational quality that has enabled us to act as critical friends and editing partners.

MVD: In my first term, I noticed that Laura was in all three of my classes, which I thought was a fun coincidence. Initially, her posts intimidated me; she always had her responses ready right at the beginning of the week, and reflected a high level of writing ability and critical thought. After a few weeks, the isolating effect of working alone in an online program was starting to take its toll on me, and I was desperate to connect with other students. I reached out to Laura to see if she would be interested in partnering with me on an assignment for our Research Methods class, and I’ve been working with her as my accountability partner and sounding board ever since. It was a little scary… I was afraid she’d say no!

LM: I was definitely thinking along the same lines as Marianne. Her posts were always exceptionally insightful and thought-provoking, and almost poetic in style. She is an excellent writer, which intimidated me at first! I was very happy when she reached out to me, as it gave me a chance to get to know her as a real person rather than to keep seeing her as another paragraph on my screen – a side effect of doing an online program that I am still not 100% comfortable with. Having Marianne to bounce ideas off of and to share learning experiences as well as frustrations with has definitely helped me feel more connected to my learning environment, and has helped me be accountable to more than just myself (which, personally, I need in order to remain on-task and on-time).

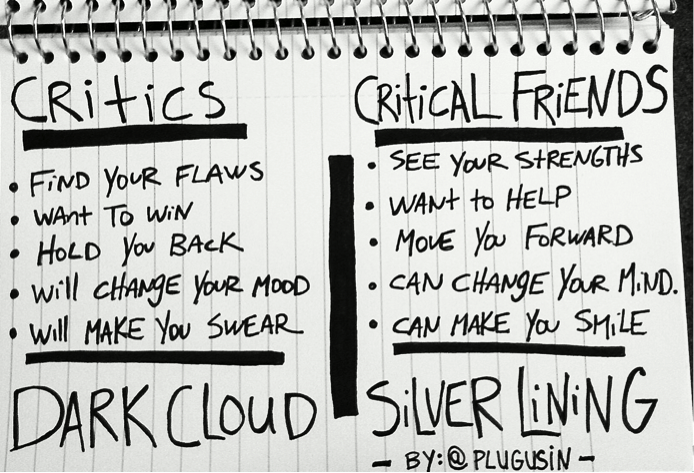

MVD: I agree. The accountability piece is huge. We worked together to set deadlines for each other for drafts and final pieces. Knowing that I had someone who I respected who was waiting to review my piece made me much more inspired to push through and get the work done. It meant that through my Fall and Winter terms, I was able to stay on top of my work and not allow it to pile up. It was also very helpful to have another set of eyes, in terms of catching APA errors, and noticing where there were gaps in the logic or in the supporting research. I would always look forward to her feedback, because I would much rather have a critical friend alert me to inconsistencies or areas of need than discover it after reading the grading professor’s comments!

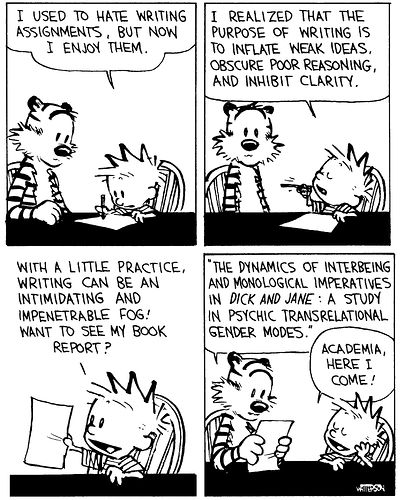

LM: Agreed! Style was a big part of it too. Knowing Marianne would review my work without judgment made it much easier to ask about specific spots in assignments that I was having trouble with stylistically. I also enjoyed having an insider to work with – a new perspective on what our professors were after, if my work reflected the course expectations, and how she thought our professors would react to my work. Obviously we would never approach an assignment from the exact same perspective, so reading her assignments, and getting thorough feedback, helped me gain new perspectives, new ideas (which we sometimes shared) and a better understanding of course material. I wonder if we had ‘graded’ each other’s work (like we did in our Research Methods course) if we would have come out with more from the experience of working with a critical friend?

MVD: I wonder what that would look like… what we do with each other is so completely subjective. Although we both work within the context of the assignment structure whenever we’re swapping our work, our viewpoints are always tempered by the fact that it is completely and totally our own thoughts and opinions. I think that provides a layer of safety; when I’m giving my piece over to Laura, I’m not expecting her to take on any responsibility whatsoever for its academic success. Having another set of eyes is really just for my own improvement and betterment; she’ll ask questions, note areas where clarification is required. She’s incredibly thoughtful and thorough. But we’ve both released each other from any kind of responsibility about the paper’s grading once it’s been submitted. Our work is just that… our own, even though we’ve had the opportunity to share, tighten, and hone.

LM: I completely agree with this, but I also feel that Marianne’s comments and suggestions have always helped me to achieve better grades (even though I never held her accountable for my grades)! I also feel that having Marianne as a critical friend has helped me overcome a lot of my anxieties about taking Master’s level courses, specifically in relation to ‘impostor syndrome’. When I started my first semester, I felt overwhelmed and like I was not keeping up academically – when Marianne reached out to me as a critical peer, I gained confidence in my position in the program and insight into the mind of another new graduate student. I think the EGS blog offers a lot of the same social benefits of having a critical peer – in that it helps connect students to the program, but I would definitely suggest going a step further and finding a critical friend. I definitely would not have had as much success this year without Marianne’s insight and support!

MVD: As we move into the next stage of our Master’s work (we’re both pursuing the thesis route) it helps to know that we’ll both be there to empathize with each other’s struggles, and also be willing to unconditionally celebrate successes. The level of detachment that exists, since we haven’t ever met each other in person, serves us well on the more objective front whenever I want honest, clear feedback, but in many ways we’ve overcome those barriers of distance because we’re able to share our stories with each other without fear of judgment. Earlier this week, I was sharing some of the challenges I’ve come up against as a researcher; I’m nearly halfway through my data collection, and sometimes when I listen to the recordings of my research sessions, I get embarrassed or down on myself because I didn’t facilitate as well as I could have, or I allowed a conversation to drift on too long before redirecting it. Laura reminded me not to be too critical, and suggested envisioning myself as a third party listening to the research as opposed to being thrown off by my own voice. It was solid advice, and helped immensely. I think the secret to our success as critical partners is empathy. We’ve both independently selected almost identical courses (5 out of 6 were the same), we’re both choosing thesis, and we’re both pushing through our own respective life challenges. Her ability to manage her workload is an inspiration, and helps me break free from moments when I’d rather watch cat videos than do actual work.

LM: I couldn’t have summarized our partnership better! Marianne is lighting the way for me as she collects data and does field work, while I am still in the process of acquiring a thesis supervisor and team… Knowing she will be there for me as I begin to research and collect data is comforting – it will be a long process for both of us, and yes, cat videos are tempting, but we will keep our course!

MVD: Moving forward, I think anyone who needs ongoing support (and really, who doesn’t?) would benefit from finding a critical friend.

What we would personally look for is:

- Someone who completes work at a pace that matches yours… were they the first to comment? The last? Find someone who has similar working speed to avoid frustration.

- Someone whose writing style speaks to you and engages you.

- Someone who is able to take a critical approach in discussion, while remaining tactful.

- Someone whose interests parallel or complement your own – (i.e., literacy and FSL complement each other, or with a similar preference for methodology)